In April, I spoke at Utopia’s San Francisco studio opening.

Utopia is an urban design and innovation firm that looks to re-imagine slums, and to develop tools to help people design their own city. A group of us were asked to speak about considerations in city design and beyond, and we had the opportunity to openly interpret this prompt:

- Barry Pousman (Institute for the Future) shared the narrative power of VR to start movements and raise philanthropy

- Karen Mok (Citizens Advisory Council of the SF Grants for the Arts) talked about the frictions in public arts funding, and why it’s important to invest in a vibrant arts community and cultural policy

- Lance Cassidy (DXLabs, Singularity U) shared his work at DXLabs, and how they’re enabling people and companies to consider and design for the distant future

I shared something very close to my heart: my community in San Jose. And the economic arrangements that we created to survive and to build our lives.

Slide from my talk: my favorite tofu house in San Jose, with prices that have not risen to match inflation or the rising cost of living in the Bay Area

Like other refugees that immigrated to the United States after the Vietnam war, my parents didn’t have much when they arrived. They slowly built a life for themselves and their families, and I credit much of this to our community and the informal economy we created to make ends meet. What does that mean? Rather than transact in cold hard cash, we traded in goodwill and services. Together, we bootstrapped toward a more tolerable quality of life.

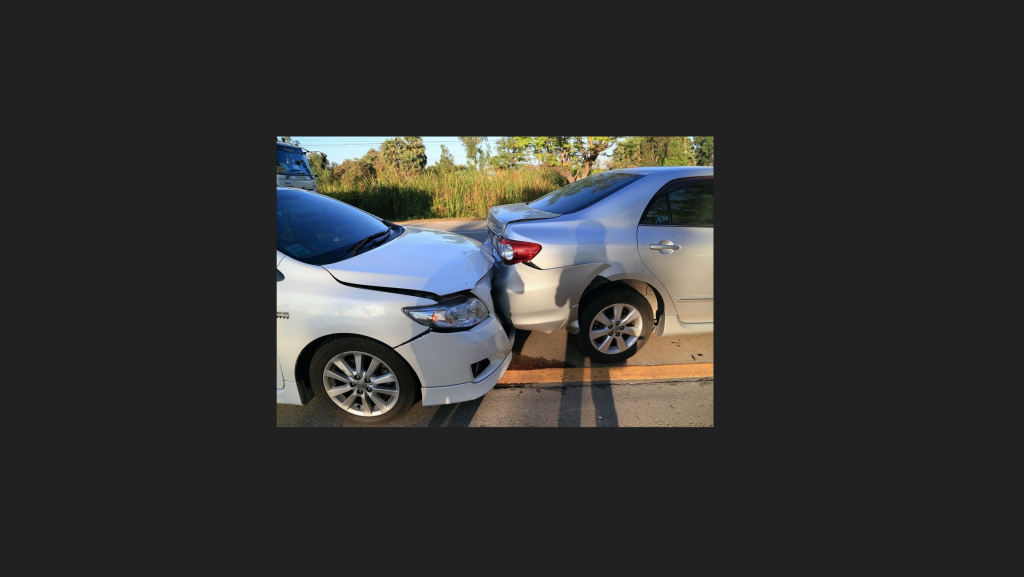

For example, I damaged my car in an accident and the local mechanic effectively fixed that car for free because my mom helped his son find a job. I was fresh out of college, I had student loans, and I would’ve otherwise wiped out my savings. I’m not unique: 44% of Americans are unable to cover a $400 emergency expense out of pocket.

Another example: my uncle – a doctor in the community – gives free health advice. In return, his patients share what they can. We get the sweetest, most mouthwatering oranges from one of his patients. This is a compelling arrangement when you compare it against the exorbitant cost of being healthy and well in our country.

Certainly, the informal economy also allows for bad actors. You don’t have to look hard to find the hundreds of vulnerable domestic workers that are unseen by our society.

But in the best way, our informal economy acted as a de-facto social safety net that we, the people, built. A safety net of our own design.

So my case to the room:

- How might we consider the informal economy in our design, while providing the necessary social protections?

- How do we create space and policy that reflect and enhance dynamics of these arrangements?